This series will recount the history of the mafia in Florida over three articles with the help of expert interviews and rare pictures. This first article will explain how the paths of settlement and expansion in Florida’s earliest days allowed mobsters to plant their seeds in the state’s landscape from the very beginning. The immigration patterns and urban development of early Florida add valuable context to trends that would endure throughout Florida’s organized crime history.

Fewer than 50 years after its admittance into the Union as the nation’s 27th state, the seeds of organized crime in Florida were beginning to sprout. In these very early days, only about a generation removed from frontier living and warring with natives, Florida was a blank, subtropical canvas ripe with possibilities and opportunities.

The land was vast. What possibilities you could carve out of the virgin state lay in the swamp, scrub, and forest that blanketed Florida’s interior, the sands that line the coastline, and the rivers that run through the state like veins, supplying essential water to the endless greenery year-round.

Some key figures in early Florida history, like Henry Flagler, Henry Plant, and Addison Mizner, took the opportunities the land provided to create things you could easily call robust or industrious at first glance, such as railroads and city developments.

Others, such as Santo Trafficante Jr. and Meyer Lansky, used the lands to craft more illicit and nefarious opportunities for themselves and others.

Business magnates and gangsters alike helped shape Florida into what it is today. While it’s easy to acknowledge the work of early barons and tycoons, the influence of the American mafia and organized crime in Florida shouldn’t be overlooked.

How the Mafia Made Its Way into Florida

Organized crime in the United States didn’t originate in Florida. Just like the seasonal snowbirds that flock to the state so commonly today, most of the mafia families that would find Florida a welcoming haven in the early days came from the Northeast originally, mainly New York.

The New England area states are much older than Florida and acted as early hubs of immigration into the United States. A combination of favorable weather and land opportunities led northerners to travel south towards the Sunshine State in the early 1900s.

Immigration into the Northeast

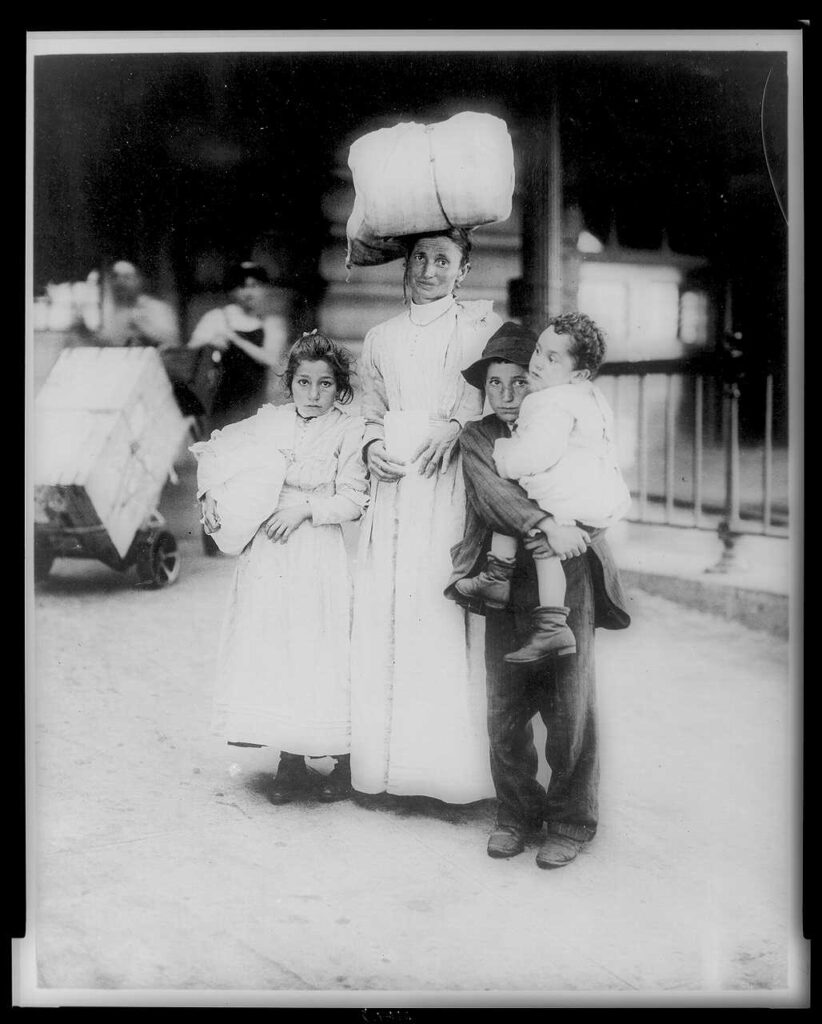

Large waves of immigrants, notably European Jews, Russians, Greeks, and Italians, were washing onto American shores in droves at the turn of the 20th century, many through Ellis Island and other northeast hubs.

Organized gangs were prevalent in New York streets as early as the 1890s. Immigrants dominated the city slums, and, as it turns out, this is where many gangs sprang up from, as these new communities were full of young men stuck together looking for a way to make a living in what to them was a foreign, new world.

As a result, early gangs often centered around heritage and ethnicity. When members weren’t actually related by blood, cultural ties in gangs and mafia “families” were very strong. Most early prominent mafia leaders were immigrants, and, simply put, the groups often looked out for their own kind, uniting along ethnic or cultural lines against a very Anglo society at the time that was new to them.

The Path to Florida

Strong cultural ties are an ever-present binding force in organized crime throughout history and even today. The different groups of Europeans from New York and the surrounding areas eventually made their way into Florida, but they weren’t the first group to do so. That honor belongs to Cubans.

Cubans began emigrating to Florida at the start of the first liberation war in their homeland in the 1860s and 1870s, known as the Ten Years’ War. Naturally, many citizens wanted to escape the strife of conflict. According to the State University Libraries of Florida, some 100,000 Cubans had sought refuge abroad by the end of the first year of the war. Florida was a common landing point due to its proximity.

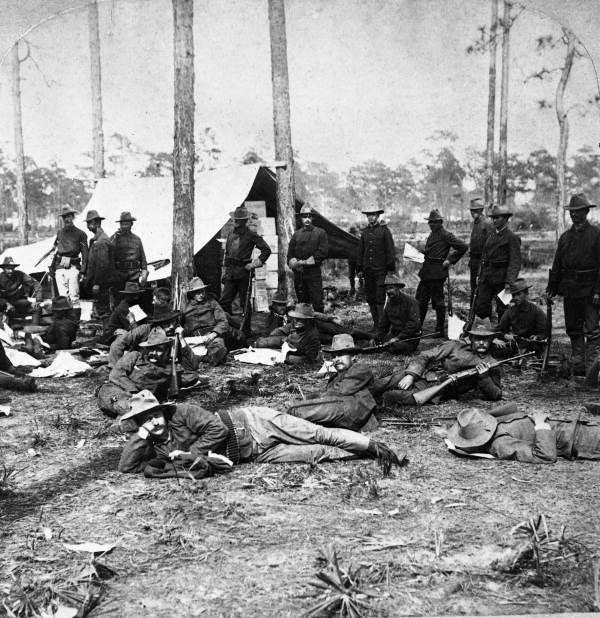

This trend would continue for years to come. According to the Library of Congress, at the beginning of the 20th century, between 50,000 and 100,000 Cubans traveled between Havana, Tampa, and Key West every year. Later wars for Cuban independence, culminating in the Spanish-American War in 1898, ensured a steady flow of people wanting to leave Cuba for nearby lands, with Florida being a top option in many cases.

Tampa Comes Alive

Enter Tampa. Around 1900, just about 50 years after Florida’s statehood, the state was far from civilized. Major population hubs were largely situated in the north of the state in cities like Jacksonville, St. Augustine, and Pensacola because they were physically much closer to the rest of the country to which Florida is attached.

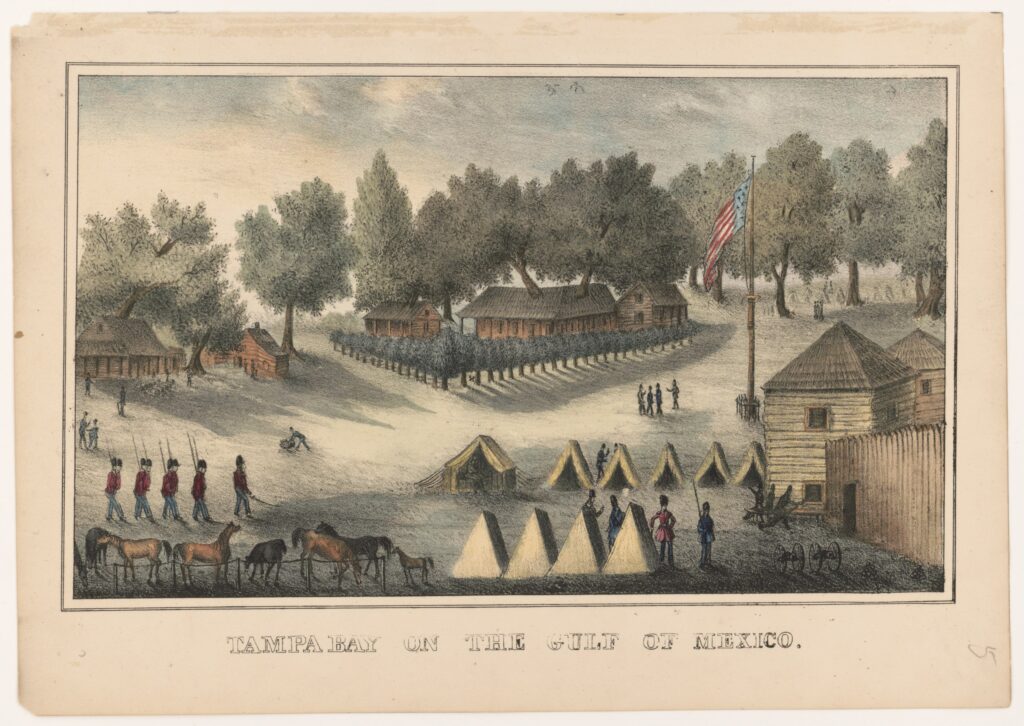

Other than Key West, Tampa was the southernmost populous city in Florida at this time by far, although it was more like an outpost. In 1850, the first census taken since Florida’s statehood in 1845, the population of Tampa was 974.

This count included soldiers stationed at Fort Brooke, a fort on Tampa Bay that was established some 30 years earlier to keep an eye on the Seminoles and other Native Americans in the unknown Florida lands.

However, development came thick and fast to the Tampa region. In the 1880s, business mogul Henry Plant connected his mighty railroad to Tampa from the north of the state. He also established a steamship line that traveled from Tampa Bay to New England and the Caribbean. These developments made immigration much easier and triggered substantial economic and demographic growth in the city. Around this time, Tampa’s mayor, who saw the city’s potential and aided much of this maritime and rail development, was John Perry Wall.

Wall, originally a physician by trade, moved to Tampa in 1869. Other than healing local residents of various ailments, his service to the city began in the mid-1870s when he became the Health Officer of Tampa. Wall’s duties as Health Officer and an active columnist in the local papers – where he showed impressive foresight for city growth – eventually earned him the mayoral seat in 1878. Wall was influential, and his family remained prominent in Tampa affairs for many years to come, although not always in the best light.

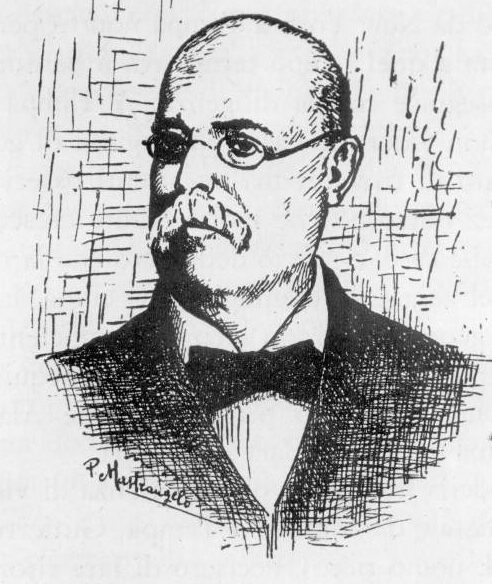

Additionally, around this time, a generous and savvy businessman named Vicente Martinez Ybor settled on a forty-acre tract of land east of Tampa after relocating from Key West in 1885. Ybor, originally from Cuba, was an experienced and successful cigar maker and was one of the first manufacturers to create and market a “Cuban” cigar in the country. Ybor and his partners bought land and planned a company town just outside the city. It quickly blossomed.

Other manufacturers followed, and by 1894, the community of Ybor City employed almost 3,000 workers in its cigar factories and became the leading center of American cigar production in the coming century. A largely Cuban, immigrant populace needing work quickly endeared itself to Ybor and the surrounding community.

And, although Fort Brooke itself was not around during that time, Tampa was a significant port for America during the Spanish-American War by 1898, adding to the growing hustle and bustle of the city.

Miami Makes a Wave

Tampa was growing by leaps and bounds. By 1895, its population exceeded 15,000 people (a 1400% increase from the 1850 census). It was the third-largest city in Florida – a young city in a young state teeming with opportunity.

With all the hustle and bustle around Tampa at this time, you might be wondering where Miami, Florida’s de-facto cultural hotspot and iconic travel destination, fits into all of this. Well, Miami was barely a balmy blip on the Florida radar.

While Tampa’s population swelled towards 20,000 around 1900, citrus farmer Julia Tuttle, along with local merchants William and Mary Brickell, just convinced railroad baron Henry Flagler to extend his east coast railroad into the south Florida region where she owned land known as Biscayne Bay Country.

In 1896, nearly 50 years after Tampa on the other side of the state, Miami was incorporated as a city, receiving 368 landowner votes of the 300 needed to officially incorporate by state standards. Flagler completed his railroad and was in the process of building a hotel in the area. The prime, picturesque, and undeveloped land in southeast Florida was about to take off. Little did everyone know, the fledgling city would become a hotspot for every mafia family in the country just decades later.

The Ingredients for Organized Crime in Florida

With Cubans arriving in droves from the south and a mix of immigrants now coming in from the north thanks to the new railroads, the 1900s were set to be a promising time for Tampa, Miami, and the rest of the state.

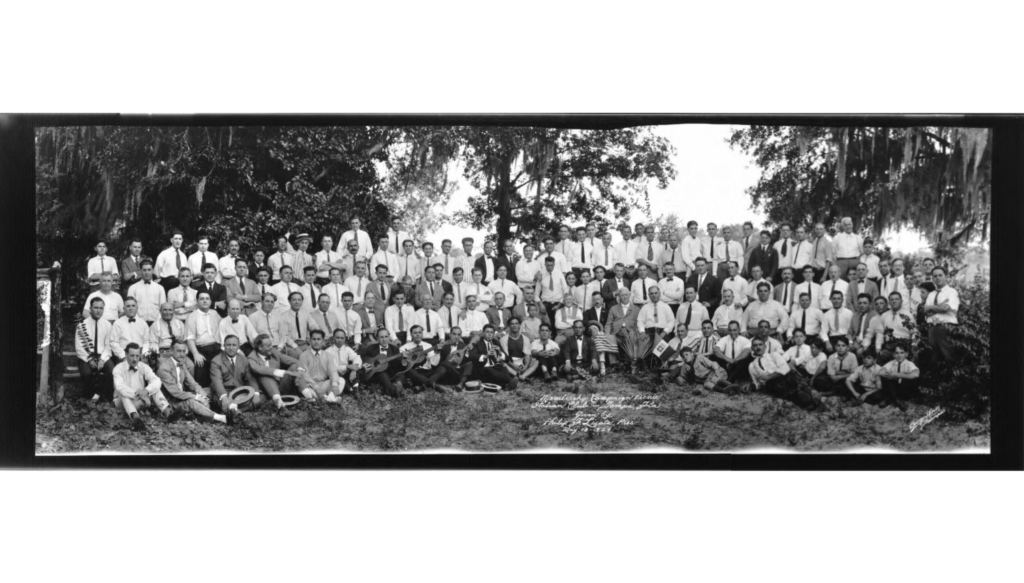

Included in these waves of immigrants were decent numbers of Italians, both working-class and wealthy. They congregated heavily in Tampa around the turn of the century, and they established a civic club very early on, the L’Unione Italiana, in Ybor City in 1912. It’s still present to this day and has a special place in the history of the mafia in Florida.

Seizing the opportunities such a paradise brings, new Florida residents began to eke out a living however they could with little regulation or oversight in place. There was a lot of money to be made, and it was only a matter of time before a felon here and a vandal there would come together and organize their criminal activity and weave their way into the fabric – or linen suits – of Florida’s big cities.

Woah! I’m really loving the template/theme of this site.

It’s simple, yet effective. A lot of times it’s very hard to get that “perfect balance” between user friendliness and visual appeal.

I must say you’ve done a excellent job with this.

Additionally, the blog loads super quick for me on Internet explorer.

Exceptional Blog!